THE YAK INTERVIEW: DAVID CORIO – PHOTOGRAPHER

Corio is one of the finest music photographers working. Here he discusses his trade and how he photographs legends, sound systems and stone circles.

Grace Jones - an icon’s icon.

London-based photographer David Corio is one of the world’s foremost music photographers – Corio prefers to shoot in B&W, both informal portraits and the high drama of concert performance, and he has followed his mentor, Val Wilmer, in focusing largely on black musicians. I wouldn’t claim to know David well – I’ve bumped into him on occasion – but I will state that he’s both an excellent maker of images and a really likeable, decent man. I stress the latter as, when I think about it, quite a few British music journalists (both writers and photographers) that I’ve met are anything but personable. Those who worked for the NME in its halcyon days often seem to have clung onto the arrogance that weekly personified. They also appear none too bright, while their interest in music appears to have ossified around the rock stars they once got to play courtier to. Thankfully, this isn’t the case with Val or David, both being broadminded, questing individuals who are generous in every sense.

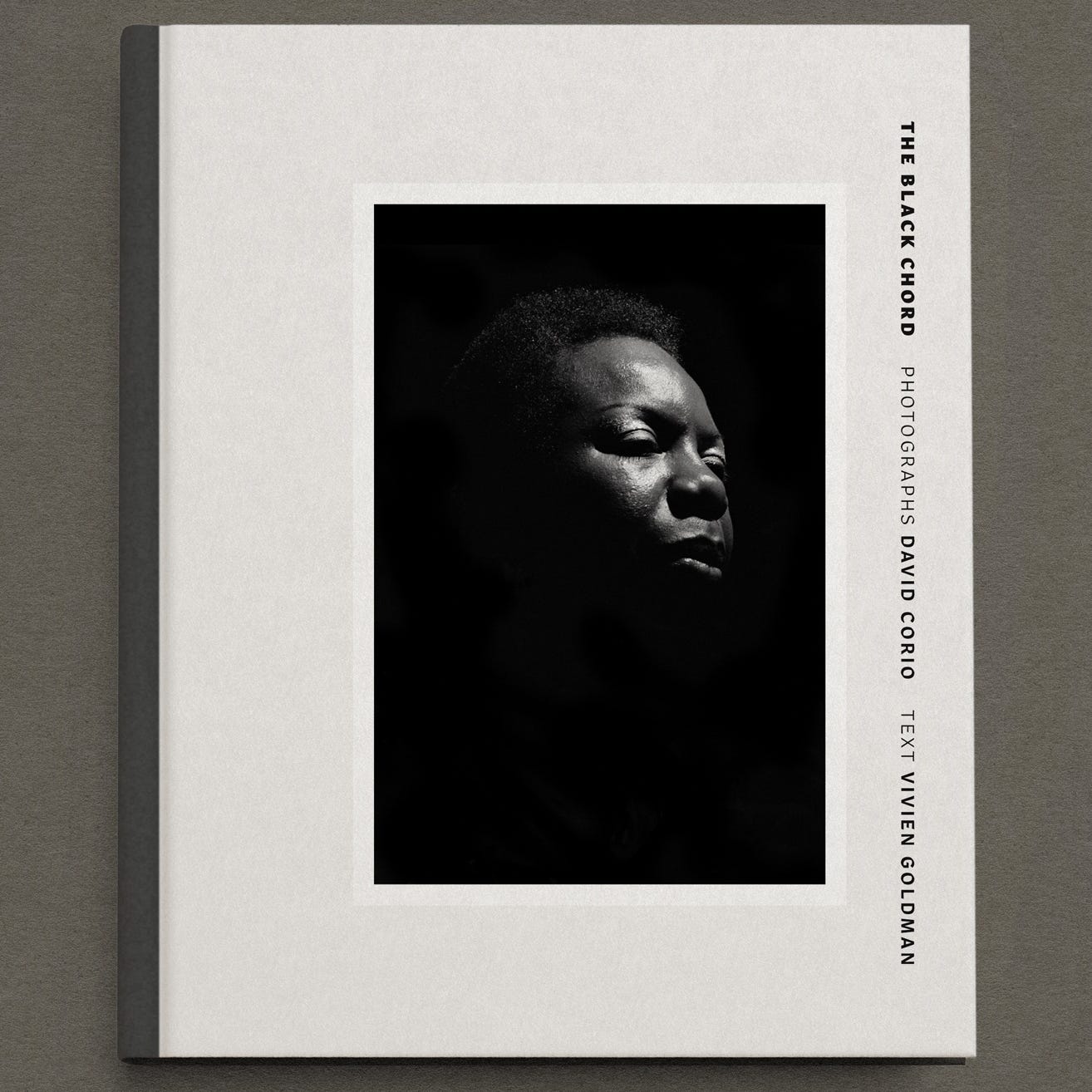

As David’s magnum opus, The Black Chord, was originally published only in the USA in 1999 I’ve never owned a copy. Thus a reprint is welcomed, published as it is on very high quality paper and consisting of over two hundred photos. It covers black musicians from across the world – Africa, the Caribbean, Britain and, of course, the USA. There are remarkable shots of musicians in Cuba and Burundi caught up in the trance-like effect of drumming and dancing, but what will ensure The Black Chord ends up on coffee tables is the plethora of photos of feted reggae, soul, rap, blues and, yes, jazz performers. Here Corio captures a very youthful Courtney Pine, Slim Galliard looking the dapper elder statesman, Art Blakey seemingly auditioning for Blacula, while his Nina Simone on stage – only her lips-nose-forehead illuminated by a spotlight - is a masterful image.

Spirit in the dark: Nina Simone

Amongst my other favourites featured here are Don Cherry playing his tiny trumpet, Sonny Rollins blowing at full throttle, Abdullah Ibrahim concentrating intensely, Sam Rivers looking wry and handsome, while Ornette Coleman appears distracted, pensive. The jazz musicians sit alongside gurning rappers, Rastas’ with elephantine dreadlocks, blues legends (Hooker, B.B., Cray etc), Salt N Pepa in full flight on stage, Grace Jones caught in the spotlight, a beautiful, healthy Whitney Houston and a waxy Michael Jackson. Corio frames his subjects in a manner that gifts them gravitas and these studies of musicians are often compelling. A handful of previously unpublished images have been added to the text of 2024’s The Black Chord (these are from the same era). Thus Corio’s book stands as a time capsule of black musicians working across the 1980s-90s – many of whom are no longer with us.

Corio’s also been busy ensuring his images get seen with three titles out on Cafe Royal, a B&W photography publisher that has done more than any other imprint to ensure photography from across the past fifty years is made available at very affordable prices (£6.70) in high quality booklets (Val Wilmer has just published her second collection, American Drummers 1959-1988, with Cafe Royal). If you’d rather start collecting Corio with something more modest than The Black Chord then his Cafe Royal booklets are the place to start: Fans & Clubbers 1978 – 1995, Reggae In London 1980 – 2004, New York City 1992-2007. I can’t recommend Cafe Royal highly enough – do check Corio and Wilmer’s editions, and all the other striking work they publish. (www.caferoyalbooks.com)

Aware that The Black Chord was being reprinted this summer a quarter century after it last came out, I reached out to David for an interview. He accepted and graciously provided a superb selection of images to grace Yakety Yak.

GC: Hi David, I picked up a free music magazine this week (Gagosian) and the cover photo was of a young Nick Cave, taken by you in 1981. I didn’t know you once covered rock music. Let’s start here, what got you into photography and how did you get started as a professional?

DC: I started off going to night school to do photography when I was 14 in 1974 and managed to get into art school in Gloucester at the age of 16. I had always liked music and gone to concerts from an early age. My sister had started dating Wreckless Eric, who was a musician who got signed to Stiff Records. He introduced me to people there, including Ian Dury and the brilliant designer Barney Bubbles and photographer Chris Gabrin, who shot all their sleeves. It was a great help to me. After college I moved to London and started to shoot shows and hand in photos to NME, Sounds and Melody Maker purely on spec. NME started to offer me occasional work and it slowly developed from there. I shot Nick Cave (then fronting The Birthday Party) for NME in 1981.

GC: As a young photographer, what photographers inspired you? Were you looking mainly at music snappers? Or at Cartier-Bresson, Don McCullen and others? And was b&w always the medium that you worked in?

DC: The two you mention there of course but my favourite - and biggest influence - is Bill Brandt as well as Andre Kertesz, Irving Penn and, on the musical side, my good friend Val Wilmer and Roy Decarava.

GC: Have you always been a freelancer? Or did you once aspire to have a staff job?

DC: Yes, always freelance. I worked in odd day jobs, Cranks restaurant, August Barnett off licence, and an industrial darkroom in the west end to be close to the music press offices. I went freelance after I was asked to go on tour with a very young U2 for NME in March 1980. I worked in a semi staff capacity for City Limits doing photography and music listings and was their Nightclub Editor for a few years in the mid '80's but got bored with that. I was asked to go on staff at the New York Times when I lived in NYC and went for an interview and, as I talked, I basically realised it wasn't something I wanted to do. So that never happened.

Lee ‘Scratch’ Perry - madman or genius? Or jester? Or all three?

GC: As your 1999 opus The Black Chord has just been republished, is it fair to say that Black music has been what you have focused on for much of your working life?

DC: I got bored with shooting white indie bands for NME and had always loved black music - originally old blues and R&B and funk and, whilst at Gloucester, got into reggae a lot. I left NME and started working for Black Echoes and did a lot of work for them every week and learnt a lot from a few writers there - Ian McCann in particular. It just really developed from there. When hip-hop became popular and reggae developed, I started to go to a lot of those shows and got to do portraits for interviews. I also did a lot for myself, so I suppose the answer to your question is, yes, although I have photographed lots of other subjects and topics as well.