ODE TO OSIBISA: WAVING FAREWELL TO TEDDY OSEI

OSEI LED OSIBISA, THE FIRST AFRICAN BAND TO WIN INTERNATIONAL POPULARITY

Teddy Osei (seated) and Lord Eric Sugumugu in Osei’s living room, April 2021. Photo: Garth Cartwright

Teddy Osei died in London on 14 January of this year. He was 89 - or possibly 92 - years old. His passing drew little attention – no obituaries appeared in the national press, no tributes (that I’m aware of) came forth from his fellow musicians. Or from young musicians who have followed in his footsteps. I doubt the likes of Mojo and Uncut are going to pay fulsome tribute to Osei. Did 6 Music or 1Xtra create slots to play his music? Unlikely. Which is unjust, as Osei was a pioneer, someone whose vision took both West African and British music forward.

Teddy Osei was born and raised in Ghana. He saw his nation gain independence when he was a youth, being inspired by Kwame Nkrumah, the politician who led the Ghanian independence movement. Osei then came to Britain in 1962, ostensibly to study music, and based himself in London for the rest of his life.

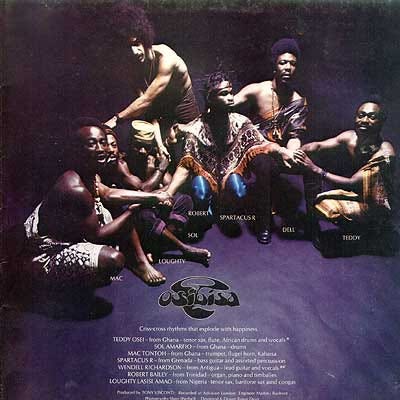

In 1969 Osei co-founded the pioneering Afro-rock group Osibisa with fellow Ghanaian musicians Sol Amarfio and Mac Tontoh, alongside Spartacus R (Grenada), Robert Bailey ( Trinidad), Wendell Richardson (Antigua), and Lasisi Amao (Nigeria).. The band's name, Osibisa, comes from a word in the Fante language, meaning "highlife".

Osibisa formed in the right place at the right time – their blend of Ghanaian high life music with rock, soul and jazz influences created a unique hybrid, one both extremely fresh and, reflecting how popular music was opening up and crossing genres, appealed to rock fans and Black music fans. Their eponymous album charted in the UK and US and, due to their dynamic live performances and willingness to tour widely, Osibisa built up a truly international fanbase: big in Africa, the Middle East, India, Thailand, Germany… Osei led Osibisa to the world and the world loved them.

I remember looking at Osibisa album covers as a child and thinking on how different they appeared to everything else in the racks. We didn’t – to my knowledge – have Africans then living in Auckland. I can imagine how wildly exciting Osibisa’s 1975 concert in Auckland was – Kiwis’ had never seen anything like it before!

I got to see Osibisa at London’s Barbican in 2015. It was a double bill of veteran Black British bands – Osibisa and Cymande (the latter having recently reformed after almost 40 years of inactivity). To be honest, I went along more interested in seeing Cymande – whose first two albums had been heavily sampled by rap producers – than Osibisa who, at the time, I mainly knew from their mid-70s hits (Sunshine Day + Dance The Body Music).

The debut album that caught the world’s attention.

Cymade’s long absence was plainly evident, as they were very rusty. Not bad but lacking dynamics, their funk felt flat. Anyone whose ever gone to see a veteran artist return to the stage after a long absence has surely had the somewhat uncomfortable experience of watching old guys struggling to get their groove on – and so it was. Then Osibisa came on - they were simply superb. Having never stopped performing, Osibisa’s Afro-rock sounded fluid and fresh, their wonderful melodies and polyrhythms spilling forth. After that concert I sought out Osibisa’s early 70s albums and became a convert.

Something else that happened not long after the Barbican concert was this: Teddy Osei suffered a stroke and would never be able to perform with his band again. Not that I was aware of this. As with his recent death, there appears to have been little attention given to his stroke – I imagine this is due to both Osibisa not maintaining a high profile in the UK since the 70s and not having a manager/press officer who sends out updates on the band.

Which means Osibisa, while acknowledged as pioneers, don’t get the kudos they deserve. Especially in the 2020s when afrobeats – as made by young singers and rappers from Nigeria and Ghana - is part of pop’s ferment. Even last year’s Beyond The Bassline: 500 Years of Black Music in Britain failed to give Osibisa the recognition they deserved – this being due to those in power who celebrate Black British music tending to look to Jamaica, rather than the UK’s former colonies in West Africa, as the source of almost all the sounds that matter. A mistake.

Here’s the debut LP’s back cover - that’s Teddy on the far right.

Anyway, in 2021 I was pleasantly surprised to be offered an interview with Teddy re a new Osibisa album being released (New Dawn, their first in 12 years). Teddy’s stroke meant this was the first Osibisa album he hadn’t played on. No matter, he still owned the band’s name and was determined to be their spokesman. My editor at The Guardian said “yes” to a feature and it was a pleasure to meet Teddy and get to hear his life story. In future he and Osibisa’s contribution will, I’m sure, be more highly valued.

I’ve developed and extended said feature below.

In the living room of a small apartment in a nondescript north west London suburb, two Ghanaian pensioners are discussing how they first met in Soho’s jazz clubs almost sixty years ago. Teddy Osei, a saxophonist and drummer, and Lord Eric Sugumugu (aka Eric Carboo), a percussionist, forged a lasting friendship “playing amongst the diaspora.” Back then Sugumugu had a gig with Ginger Johnson and His African Messengers - one of the first British African bands - while Osei was playing with Dudu Pukwana, the celebrated (and self-destructive) South African jazz saxophonist.

Lord Eric is ebullient, leaping out of his seat to exclaim about their role in making the Sixties swing – amongst many other things, he was part of an African drum troupe the Rolling Stones employed at their 1969 Hyde Park concert. No, Teddy notes, he wasn’t there but he did join the Stones to perform Brown Sugar on Top Of The Pops. Osei is a stroke survivor so remains seated and speaks quietly. So quietly his management suggested I do the interview at his home – a rarity in our Covid-age of Zoom chats – but a wise one, as Teddy’s voice rarely rises above a whisper.

As founder and leader of Osibisa, Osei is an unsung pioneer – one could label him the “godfather of afrobeats” - and now, with a new album out, he wants to tell his story. Best known for their two mid-1970s hits (Sunshine Day and Dance The Body Music), Osibisa never conformed to genre: mixing Ghanian highlife music with jazz, soul and rock (later funk and disco), touching many bases over the past half century. Your sound was prescient, I say, and Osei nods agreement then begins to speak.