BELLA ITALIA: THE PUGILIST AT REST (2000+ YEARS)

MO' ITALIAN NOTES: THIS TIME ON ANCIENT ROME, THOM JONES, DAVID TUA & OTHER NOBLE WARRIORS

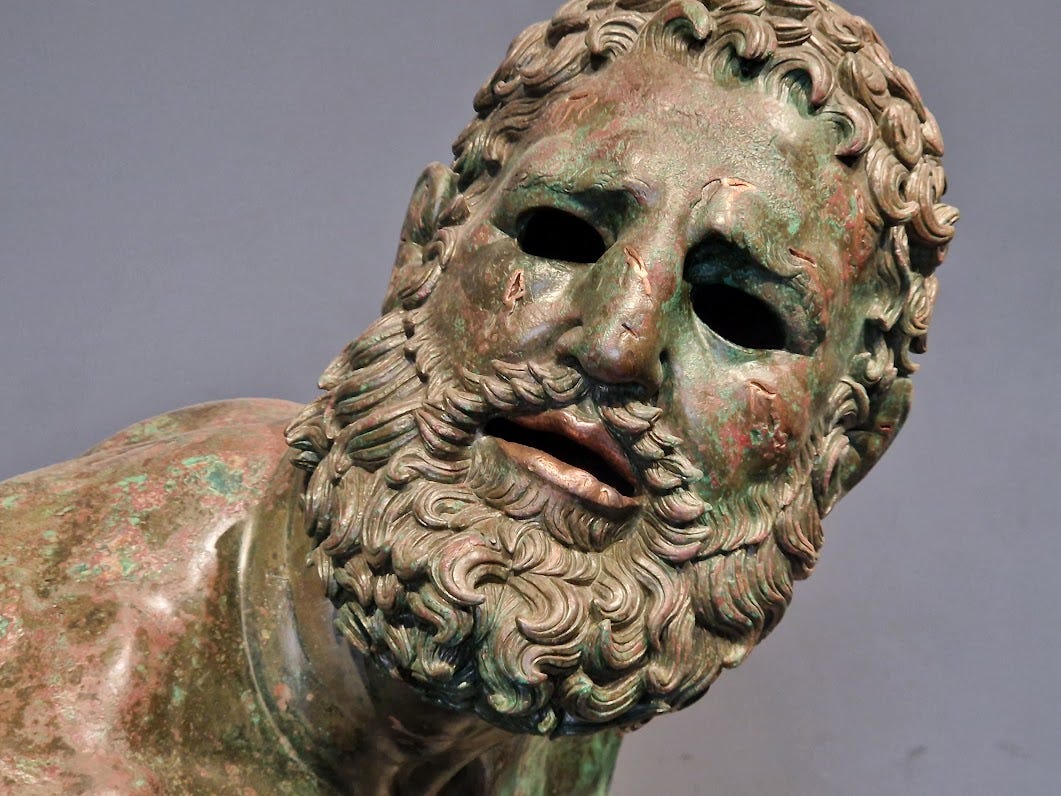

The face of a fighter: 2000+ years ago the subject of this sculpture fought in Greece.

Beyond ogling my favourite old masters, while in Rome I also set out to engage with the city’s antiquities. A good place to begin is the Museo Nazionale Romano: Palazzo Massimo alle Terme. This three storey museum, almost next door to the central train station, is jammed with frescos, mosaics, sculptures and more from 2000+ years ago. As you might imagine, there is much here to observe.

As I strode these hallowed halls I kept thinking of the following: the vanity those in power display in their busts, the always predictable fashions of the ruling class (as revealed in their art and textiles), ultimate power leading to extreme decadence (a notable exhibit are the huge bronze beast emblems that once decorated Caligula’s huge, luxurious Nemi ships – how very oligarch), and how empires crumble and life can be so much folly. “A tale told by an idiot full of sound and fury?” Something like that.

Anyway, I find it fascinating, reflective of both the ancient empire once run from this city for centuries, and of our late-capitalist society: the disintegration of the British Empire 75+ years ago birthed many more equitable societies (and, in the likes of Egypt, Pakistan and Yemen, extremely inequitable ones), yet today new barbarians are storming our gates, determined to do away with equality/democracy, employing social media rather than armies with battering rams, mining fear and loathing, playing on ignorance and grievance. “The Earth is littered with the ruins of empires that once believed they were eternal,” wrote Shelley and so might be the case again as Putin and Trump and their acolytes wreak devastation.

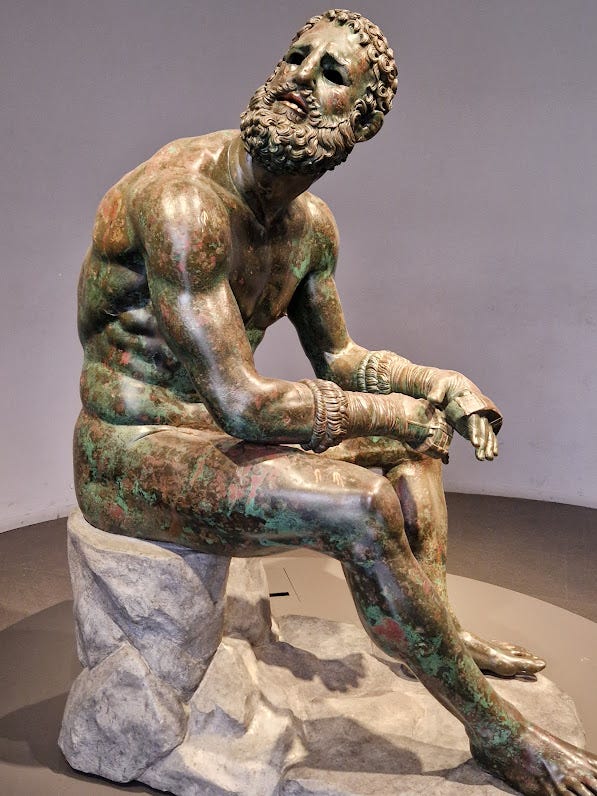

One such piece of “litter” held in this collection is a bronze sculpture I bow before every time I’m in Rome: the Pugilist at Rest. This bronze work was discovered in the late 19th Century during excavations in Rome and had, by then, purposely been buried for well over a thousand years (to protect from invading Visigoths? No one knows), which is why it is in such remarkable condition (most bronze statues from antiquity ended up melted down).

The Pugilist at Rest is a life-sized Greek sculpture of a man, seemingly in early middle age, seated whilst glancing over his right shoulder – someone has attracted his attention. He is, as the statue’s name suggests, a boxer: his hands are bound with the leather straps ancient fighters employed to protect their knuckles, his nose is broken and his face scarred, drops of blood are evident on his face and arm. The pugilist is recovering after a fight, taking time out, at rest.

Fists of fury: were they still wrapped because the sculptor requested so? Or was the pugilist soon to fight again?

This bronze work is as accurate a portrayal of the seasoned professional fighter as any ever created. You sense the pugilist’s weary exhaustion, the hurt and stoicism. To be a boxer in ancient Greece then, this being your trade, you surely continued to fight until, finally, an opponent beat you to death. Or boxers’ ended up so damaged that the men who controlled prize fighting no longer insisted they wrap your hands with leather straps. Not that different then from today.

This muscular boxer has recently fought, the bronze having been treated to suggest drops of blood on his face and right arm, while his sightless gaze is eerily effective (he once had eyes, likely made out of ivory). Information in Italian and English notes that the pugilist has a “penis infibulation” (a ring, attached with a pin through the foreskin to fasten it above the penis), which I’d never heard of before; having looked it up, I’ve learnt these were employed by athletes in the ancient world and on slaves.

There’s also information on the remarkable bronze casting technique employed to create the sculpture – the sculptor’s name is lost to history but what a skilled artist he was. As with Velasquez’s painting of Pope Innocent X, the sculptor managed to capture the essence of his sitter, gave an insight into the soul of a man who surely was celebrated for his ability to deliver violence to opponents (and soak up punishment). Here he sits, this now anonymous boxer from ancient Greece, letting us who gaze upon him know how little has changed across millennia when it comes to human behaviour.

Think about it: in his time the pugilist may have been as famous, as revered and loathed, as Mike Tyson is in ours. Yet its not his gift for violence that ensures he is gazed upon daily more than two thousand years on. No, its the skill of the sculptor who managed to capture in bronze the weary essence of this stoic fighter.

This ‘skill’ seemingly faded as Greece passed into a backwater – sculptors continued to carve men out of stone and bronze but none came close to the ancient Greeks for their observation and drama. Thus the Pugilist would have been valued in ancient Rome - none of the local sculptors could match the artistry and insight here. Just as no sculptor today can convey such insights into being human. And no painter can capture the violent erotic tensions that dance through Caravaggio’s canvases. Which is why some of us continue to return to this city.

I first learnt of the Pugilist in January 1992 in, of all places, Egypt. I was a backpacker and had travelled through December and into January across Rome, Greece, Turkey, back to Greece, a ferry to Israel/Palestine and, finally, Egypt, where the sun shone and there was a US Cultural Consulate (in Cairo or Luxor? I can’t recall). I dropped in one day and, having been on the road for so long, wanted to refresh myself with news. This was way before the internet had made its presence known, ensuring newspapers and magazines were highly valued.

Flipping through a New Yorker I saw there was a short story called The Pugilist At Rest. At the time I paid more attention to boxing than any other sport – in 1989 I’d written a feature on young Polynesian boxers in Auckland, one of whom, David Tua, I now knew would soon be heading to the Barcelona Olympics – so the title hooked me and I started to read.

This is the book. Highly recommended, if you enjoy reading on damaged, violent men.

I’d never heard of the story’s author, Thom Jones, but upon finishing I knew I would read more of his stories. The Pugilist At Rest is narrated by a Vietnam veteran, he starts by recalling Marine Corp training, then combat in Vietnam - which he survives unscathed, only to suffer a beating not too long after in the boxing ring. And this beating has left him suffering from epilepsy – his failing health making him increasingly fragile.

Throughout the story, which rips along and is packed with laconic asides, the narrator references the Pugilist at Rest sculpture in Rome, alongside Dostoyevski (who suffered also from epilepsy), Schopenhauer and more. The Pugilist At Rest is a remarkable short work of fiction, very entertaining (Jones writes with bravado – convincingly detailing macho, gung-ho, young guy stuff) while also meditative, describing how ageing and health problems will reduce the most virile of men into frail, vulnerable individuals.

At the time I didn’t note down Jones’ name so, whenever I thought of the story, I recalled its title but not author. Then, one day in 1994, in a Charing Cross Road bookshop, I saw a collection of short stories called The Pugilist At Rest. Of course I bought it. There was the title story – I’d later learn it was the first story Jones had ever had published, he really was an ex-soldier and boxer who wrote the story while working as a janitor, sending it to the New Yorker without any introduction – and ten more, all in a similar vein and engaging, if none matching the Pugilist.

I’d purchase Jones’ next two short story collections – the New Yorker and other US publications championed his work, seeing him as a contemporary writer who covered war and boxing, male isolation and suffering, like a contemporary Hemingway. But reading these efforts was akin to buying the second and third albums by a rock band who stunned you with their debut single then kept trying (and failing) to replicate its dynamic. They all felt a bit tired, somewhat forced.

So I never read Jones again. Or gave him any thought, except for the first time I visited Museo Nazionale Romano and came across the Pugilist at Rest. This may have been twenty years ago. Prior to that I wasn’t even sure the sculpture existed: Jones’ story is fiction so he easily could have invented a sculpture of an ancient boxer. I was impressed, and possibly re-read his feted story when I returned to London. Then in 2016 I learnt Jones had died, aged 69. Seemingly, he published no further books after those first three collections of short stories. I guess it wasn’t only me that felt his writing was falling off. Anyway, he wrote one truly remarkable short story and that’s more than most writers will ever achieve.

The Samoan pugilist resting in his Auckland gym: David Tua, now retired from fighting.

As mentioned, I used to take boxing very seriously. I loved watching it ever since when, as a child, Muhammad Ali’s fights were shown live on Kiwi TV (and always seemingly late afternoon, so I’d run home from school and watch him battle the likes of Ken Norton, Joe Frazier and George Foreman). Ali’s reign was followed by the age of the four middleweight kings – Sugar Ray Leonard, Roberto Duran, Tommy Hearns, Marvellous Marvin Hagler – and they engaged in epic, highly skilled battles, the noble warriors of that age. Back then no other sport matched professional boxing for its powerful characters and fierce rivalries.

At the same time I came to understand how boxing is loathsome: training your muscles and mind so to hurt your opponent, to damage their brain. As boxing is now almost always on pay-per-view I miss everything except the huge fights – Fury vs Usyk – which I make my way to a pub to see. The contradiction – this is exciting! Yes and this is barbaric! - remains and still I cheer the likes of Usyk on.

David Tua, who I wrote about when he was a gifted schoolboy boxer, went all the way to the top, proving himself to be a true gladiator as he regularly knocked out bigger fighters, encountering his nemesis when he fought Lennox Lewis for the world heavyweight championship. He lost on points – Lewis was a lot taller and jabbed Tua for 12 rounds, careful to not let the stocky Samoan get close enough to land one of his powerhouse punches - but what an achievement.

Later, like many boxers, Tua appears to have lost much of his fortune via poor management. Recently I heard he and his wife were returning to Samoa to live. I hope David is enjoying the quiet life and not suffering from injuries inflicted in the ring. Like the ancient Greek boxer captured in bronze, Tua may now sit stoically, reflecting on his glory days while living on the Pacific island of his birth.

Thinking of gladiators reminds me to mention how I also knew Russell Crowe when we were teenagers in Auckland. When Crowe won the Academy Award for Gladiator I must admit to feeling a degree of disbelief – Russell, at 17, wanted to be a pop singer (he traded as Russ le Roq) and was incredibly inept. A joke, even. That he would develop into a skilled actor surprised the hell out of me. Well done, Russ. And he made a much more effective gladiator than Paul Mescal, I’m sure you all agree.

Anyway, enough from me. Seeing the Pugilist sitting in his mighty silence in Rome inspired me to share a few thoughts. If you have made all your way through this piece then, as a reward, here’s a link for the Saturday Night Live sketch as mentioned on my previous Bella Italia post. Its about blokes like me obsessing over ancient Rome. My pal – and fellow writer – Aaron Cohen first alerted me to it. Thanks, Aaron.

This is very funny - worth casting your eyeballs on.

Aaron added as a note (he is a teacher) “It's mostly accurate, but there's one thing that a lot of people don't know: while the statue of mythical Rome founders Romulus and Remus being nursed by a wolf is ubiquitous, it may not depict the whole truth. Mary Beard in her book, SPQR: A History of Ancient Rome, mentions the Roman author Livy who wrote that the Latin word for wolf ‘lupa’ was also slang for ‘prostitute’. So that may have been who nursed those two. Anyway, that's the fun thing about myths: feel free to interpret, reinterpret as you wish.”

Last word, as ever, to Percy Shelley

"My name is Ozymandias, King of Kings:

Look on my works, ye Mighty, and despair!"

No thing beside remains. Round the decay

Of that colossal wreck, boundless and bare

The lone and level sands stretch far away.”

THANKS FOR READING. IF YOU AREN’T YET PLEASE CONSIDER SUPPORTING MY WRITING BY BECOMING A PAYING SUBSCRIBER.

What a man: immortalised in bronze, the pugilist reminds us how ever those who are tougher than the rest must fade to dust.