For an artist who hasn’t released a new album since 2008’s Our Bright Future, nor had a hit since 1995’s Give Me One Reason, or performed for her fans since 2009, and avoids social media – actually, avoids almost all media – Tracy Chapman has a remarkably high profile right now.

I should state that Chapman soared back into the spotlight when, in 2023, country singer Luke Combs covered Fast Car – the song that made her famous and remains, to this day, her most beloved song – last year and enjoyed a huge US hit. This lead to Chapman joining Combs on stage to sing Fast Car at the 2024 Grammy Awards. Both the return of Chapman to a stage - and that she was sharing said stage with a young, white, male country singer – proved sensational.

Most artists would use the opportunity of their Grammy performance to announce how they have a new album or tour (or merch’) forthcoming. Not Chapman. But she has broken her long silence this week to give an interview with the New York Times.

Why? Well, she’s just reissued her eponymous debut album on vinyl – Chapman discusses how she ensured the recordings were correctly remastered for the occasion. Not really a big deal considering said album has already sold over twenty million copies and a decent proportion of those in 1988/89 would have been LPs (CDs only really took over physical retail in the 90s). This said, I have noted used LP copies of TC gaining higher prices in recent years (while the CD remains a couple of quid), so the demand is out there for a vinyl reissue. And in the NYT interview Chapman suggests her perfectionism over the remastering means the album was held up for some two years. Hopefully for all involved the new pressing sounds superb.

Because Tracy Chapman is an album I’ve never tired of listening to. Not that I’m a crazed fan boy who considers the album a “masterpiece”. It features several weak songs (Why is just dire), and I dislike some of the sweeteners that producer David Kershenbaum adds (on Baby Can I Hold You Tonight, my and everyone else on earth’s second favourite TC song, he employs strings to add emotional pathos when they are so unnecessary – Chapman’s extremely expressive voice conveys every emotion necessary – and the backing musicians are sometimes obtrusive: I’d love to hear these songs with just a string bass + maybe a pianist or lap steel player backing TC). Or just Tracy, voice and acoustic guitar.

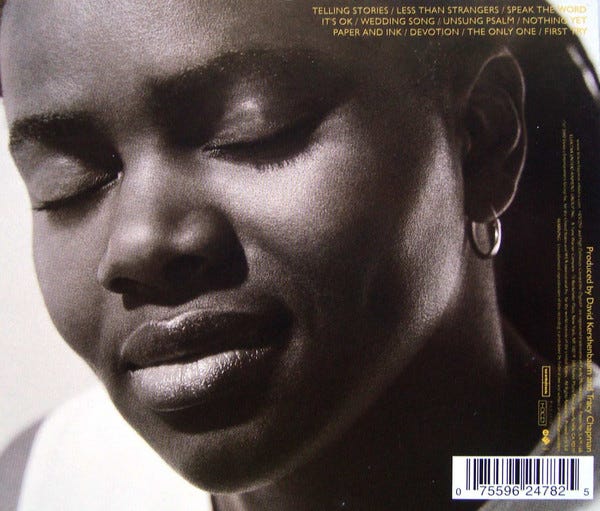

I get it: Kershenbaum was hired to make an unknown folk singer’s songs palpable for pop radio in the late 1980s. So he tweaked and sweetened. Thankfully, Kershenbaum never went OTT – some producers of that era would have added orchestras or choirs of backing vocalists or rock guitar solos or synthesiser beds (actually, some would have added all of these), intent on blanding Chapman’s sound into pop mush. Overall, I think TC remains both an impressive debut and a good listen. Matt Muhurin’s portrait of Chapman that graces the cover perfectly fits both music and artist – pensive, quiet, thoughtful, intelligent, private and soulful.

My then partner Erika and I certainly listened to TC often. Even though her songs are concerned with hurt and alienation we still found it very intimate, a record to cuddle up and listen to. Erika was at art school and she was struck by the TC cover, that single duotone portrait conveying so much. Funnily enough, back then I listened to lots of rap and Jamaican dancehall – pure testosterone music – and Chapman, in her quiet, feminine grace provided a counterpoint to this.

Which surely helps explain the album’s success: when the charts were full of U2, Bruce Springsteen, Guns N Roses, Prince, Bobby Brown, Madonna, Whitney and other artists not known for their subtlety, Chapman sounded calmer, deeper, less frazzled. And she had a social conscience. For Tracy Chapman reveals a singer who understands that society is unjust and working class people (especially Black, working class women – tho’ she never sings in slogans: except on Why) are second class citizens. She sings of dreaming of a revolution that will make things better, then running away from a dreary job on a supermarket checkout with a new partner who has a fast car. She sings words like “sorry” and “forgive me” with greater emotional heft than any singer of her generation. And when she sings “I love you” the listener is convinced. Her voice aches, beautifully so. Heartfelt? Indeed.

And it was a handful of songs – the TC album has four or five standout songs, the rest are slight – and that beautiful, solemn voice that carried her to huge fame. While there have been several other Black female folk-inspired singer songwriters prior to Chapman – Odetta and Joan Armatrading being the most successful – Chapman didn’t emulate them. Later on she would claim to have been unaware of their music (and folk music in general), having grown up on country music via the Hee Haw TV show her mother loved to listen to, alongside US DJ Kasey Kasem’s American Top 40 (which I also listened to religiously as a child when it was broadcast on Radio Hauraki on Sunday’s).

In Elektra Chapman had a powerful record label behind her, one that instinctively sensed they’d signed a rising star. And the public, after so much bombastic synth pop and stadium rock, was hungry for a fresh, acoustic voice. Lucking in to a primetime spot at the Free Nelson Mandela concert at Wembley Stadium in June 1988 (she’d initially been booked for - and appeared - on an afternoon slot but, when Stevie Wonder couldn’t take the stage that evening due to technical problems, Chapman stepped in as headliner, so winning over millions of visitors with the eloquence and directness of her performance). Her album had barely been out six weeks and this unexpected prime time slot back when everyone interested in music paid attention to the same media anointed her a star.

Zadie Smith, then aged 12, watched Chapman on TV with her family and recalled here the profound impact she made. https://www.theguardian.com/music/2025/mar/31/zadie-smith-tracy-chapman-debut-album-free-nelson-mandela-concert?

Not that Chapman appeared to enjoy fame. She rarely gave interviews and never did the things expected of rising stars: attending exclusive award shows/parties, flaunting their partner/new found wealth, turning up on MTV, making expensive, showy videos, goofing on chat shows. Instead, she retreated into herself and went to work on a sophomore album. Considering the TC album was now selling millions and millions of copies worldwide – it has since sold over 20 million – there was real excitement around the release of Crossroads in 1989. I recall the guy who looked after Elektra’s account in Auckland breathlessly telling me how he’d heard a test pressing of Crossroads and it was going to blow minds.

It didn’t. Instead, 1989’s Crossroads bore all the hallmarks of “difficult second album”. Chapman had written the songs on TC as a complete unknown - Talkin’ ‘Bout A Revolution was written when she was 16 (yes, it sounds it) - working on them while studying anthropology in Boston. They were her life (so far) and, beyond busking and singing at the occasional campus anti-apartheid protest, she hadn’t even worked the local folk clubs. She was a novice who suddenly found herself hugely famous and successful. And instructed by Elektra to deliver a follow-up. Well, Tracy duly did so. But the songs lacked spark.

Crossroads isn’t a bad album. I like how, with Chapman now co-producer, she stopped Kershenbaum from sweetening her songs. Her voice is strong and there is some imaginative instrumentation. But none of the songs demand you play them again and again. Sales slumped and audiences turned away: I recall her playing at Shepherds Bush Empire, a 2200 seater, in the mid-90s, where seven years prior she would have filled an arena. Her reluctance to engage with the media meant she attracted little attention and the albums that followed Crossroads didn’t excite anyone but the faithful.

To be honest, when I thought of American female singer songwriters in the 90s it was the likes of Lucinda Williams and Annie DeFranco who struck me as releasing exciting new music. So, when I was approached by the London PR who looked after Elektra/Warners artists asking as to whether I would be interested in interviewing Chapman, I was surprised.

Tracy from the Telling Stories inside sleeve. This is how I remember her looking when we met.

It was an odd offer: normally PRs pitch the artist to the journalist months in advance (so you have time to approach different publications). This time it appeared that Tracy was in town. And available for interview. It was a yes or no call. This must have been around 2000 when her album Telling Stories was released. It appears that the album had sold well in France but poorly in the UK (one week at no 85 in the charts) and Elektra had convinced her she needed to do some press.